Turning Plastic into Art

For those who have ever watched the 1967 rom-com The Graduate, you probably remember the scene in which Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) is urged during his graduation party to join a business dealing in plastics. At that time, no one appeared even vaguely aware of the disasters this “material of the future” would wreak upon the planet we call home. We, in that very future, are only too conscious of the unintended consequences that the proliferation of plastics has on the environment and its creatures. This is where art can step in and play a role. Artists have the capacity to raise awareness about such issues and transform garbage into artwork that provokes, amuses, educates, and stimulates us to rethink our own consumption habits.

You Made That with Plastic? Turning Trash into Treasures. Burnett Gallery, Gualala Arts Center, Gualala, CA.

Inspired by artists who have been tackling this monumental environmental crisis, I decided to propose an exhibit on art made with plastic trash and asked Paula J. Haymond to be my co-curator at the Gualala Arts Center (April 12 - May 5). We invited artists from the San Francisco Bay Area and Mendocino/Sonoma coast to create interesting, playful, beautiful, and powerful objects by upcycling plastic that’s found on our beaches, in our homes and workplaces, restaurants and cafés. They demonstrate what’s possible when we make the effort to keep plastic off our streets and roads, waterways and oceans, and out of garbage cans and landfills.

In the image above, you can see objects that start on the floor and climb up the gallery wall—our dirty footprints on Mother Earth. Beth Hartmann was inspired to knit them from used plastic bags when she heard about the quantity of plastic in our oceans. Globally, an estimated 8 million metric tons of plastics enter the ocean every year, roughly equivalent to dumping a garbage truck full of plastic into the waters every minute. She also kept seeing plastic bags caught in fences and shrubs and said, “I imagined a time when we couldn’t see or touch the earth but would have plastic everywhere between us and it.”

Planet Earth Screwed: Polluted, by Phyllis Thelen. Photo courtesy of the artist.

An experimental artist whose sculptural forms are created out of the materials found in nature, Phyllis Thelen, a resident of San Rafael, is also touched by ecological events. All of her work, including the series Planet Earth Screwed, is about defending, protecting, and celebrating nature. In the image above, she used plastic to make her point.

Dis-Charge, by Alex Friedman.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Plastic bags abound, but so do plastic cards. At her tapestry studio in Sausalito, California, Alex Friedman embellished Dis-Charge with numerous cut up credit, library, membership, and affinity cards. Accustomed to weaving with natural fibers, she remembers being hesitant at first to add plastic. But she decided that the issues are important and, by addressing them in this way, she might make viewers think about the amount of plastic used daily. “This piece reflects my concerns about all the plastic waste that ends updegrading our oceans and sea life,” she says. Plastic bags and flexible packaging are the deadliest plastic items in the ocean, killing such wildlife as whales, dolphins, turtles and seabirds around the globe. Alex adds, “The credit cards are a further commentary on the ongoing excessive material consumption in our present society.”

Widening Gyre, by Judith Selby Lang. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For 25 years, Judith Selby Lang and Richard Lang have been picking up plastic debris from Kehoe Beach in the Pt. Reyes National Seashore and creating installations in worldwide locations. Their barn in West Marin is filled with bins sorted into multi-sized pieces of a particular color or multiple examples of a particular item. When invited to participate in You Made That From Plastic? they sourced their barn inventory and made a big pile of just the black plastic that was not painted black, but was the color as found on the beach. With a message about the relationship between plastic and oil, on top of the pile, they mounted a black toy ATV, also found on the beach. The Langs pick up even the tiniest pieces, noting that plastics in the oceans break down into smaller and smaller pieces—microplastics—which act like magnets for pollutants. Some become tiny enough for zooplankton to consume and are eventually ingested by fish and in turn as seafood ingested by humans. One in three fish caught for human consumption now contains plastic.

Pile It ON, by Judith Selby-Lang and Richard Lang.

The wall hangings behind Pile It ON are wedge weave tapestries by weaver Deborah Corsini of Pacifica. [In between them are necklaces fashioned with plastic by Judith Selby Lang.] Although wool and natural fibers like silk, cotton, and linen are Deborah’s usual materials of choice, the chance to experiment with non-traditional ingredients has been both challenging and alluring. The bright yellow of the plastic bags — from a San Francisco Chronicle subscription in the 1980s — were too dazzling and seductive to discard. Even in a close-up of Adrift, a small piece, it’s difficult to tell that the yellow once contained a daily printed newspaper, now a thing of the past.

Adrift, by Deborah Corsini.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Like the Langs, Robin L. Bernstein and Ken Kalman, artists in the Bay Area and North Coast, decided to collect beach plastic, in their case, from four nearly pristine northern California beaches (Seaside, DeHaven, Howard Creek, and Pete’s). Normally, they would pick up trash and litter to toss or recycle but, with the art project in mind, they picked up nearly every bit of plastic they came across, and most were very small. It angered and surprised them that, even though the beaches looked free of litter, they were not. For 10 months, they walked hunched over, heads down, arms extended, appearing to be harvesting tiny things from the sand and rocks. Where once they had looked for shells and rocks, bones and bait, now they were singularly focused on seeing and clearing away those things that did not belong in a natural setting.

Everything On It: A year of collecting on 4 pristine and rugged North Coast beaches, by Robin L. Bernstein and Ken Kalman.

Photo courtesy of the artists.

Considering the effect of plastics on marine life, Sharon Nickodem, a coast artist with a passion for photography, collage, and mixed media, created a humorous piece, Trophy Fish—NOT. But she also wanted it “to be a visual commentary on the state of our oceans and the impact on the creatures that live there.”

Trophy Fish—NOT, by Sharon Nickodem.

In Bleached, Berkeley physician-turned-artist Ruth Tabancay addresses the catastrophe that has befallen coral. She explains, “One of the main causes of global warming is the burning of petroleum-based fuels which, among other applications, are also used in the manufacture of plastics. An increase in ocean temperature, as little as 2° Fahrenheit, can be deadly for coral reef systems. Corals form a mutualistic relationship with the algae zooxanthellae. Warmer temperatures cause them to expel the algae and, if sustained, eventually kill the corals. Instead of stunning colors, a skeleton is left behind.” Bleached is composed of stylized crocheted coral structures that are interspersed with reef “organisms” crafted from plastic medical waste. The waste components were the result of Ruth’s pulmonary disease worsening to the point of necessitating a lung transplant in order to survive. Afterwards, she had to inject herself with medications through disposable plastic delivery systems. While these treatments were essential, the accumulation of plastic debris conflicted with her strong commitment to reduce as much as possible the amount of plastic in her life.

Bleached, by Ruth Tabancay.

Detail of Bleached, by Ruth Tabancay. Photo credit: Dana Davis.

Jennie Henderson, a long-time Mendocino coast resident and award-winning weaver who works with natural fibers, used the plastic twine (formerly metal wire) from hay bales, along with other plastic throwaways, to create 100% Trash. She also made a small circular rug out of Wall Street Journal plastic sleeves that her sister gave her.

100% Trash, by Jennie Henderson.

Wall Street Journal Rug, by Jennie Henderson.

San Francisco artist Jerry Barrish collects objects for his assemblage/constructions on the beaches, bayshore, roadways, and recycling centers near the city. Over time, he became enthralled with working with found plastic items. He employs a hot glue gun almost like a welding torch, which he used to wield on copper and steel almost 50 years ago. He says, “Sometimes I set out to make an image and actually search for the pieces to complete the idea, but more often it's the found object that dictates what I'm going to do…[for] inspiration and freedom come from letting this discarded stuff of our society provide the image itself. My natural bent as a storyteller becomes obvious with the figurative nature of subjects.”

Puppy Dog, by Jerry Barrish. Photo courtesy of the artist.

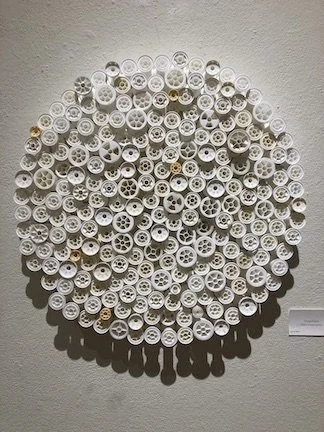

If you’re a fiber artist, you might wind up sewing with a lot of thread. What do you do, then, with all the plastic spools that are left? Unwilling to simply throw them away, Juline Beier, in Sausalito, created a kind of mandala with what she had accumulated for many years.

Threadbare, by Juline Beier.

Although we use plastics sometimes only for a few moments, they are made to last forever. Plastic doesn’t simply disappear: bottles, disposable nappies, and beer holders take 450 years to degrade; straws can take up to 200 years and Styrofoam cups 50 years. So Gualala painter and sculptor Bruce Jones decided to turn empty bottles into a balancing act.

Falling Down, by Bruce Jones.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

On the northern end of the Sonoma coast, Donnalynn Chase works primarily with antique images from discarded books, aged etchings, and childhood and collected ephemera of days old to make art. Challenged to create something with plastic trash, she decided to do what she loves to do with heavier papers and fabric–bundle them with threads. She realized she had plenty of material: the many plastic wrappers that abound from basic shopping.

Cast Offs, by DonnaLynn Chase. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Tess Felix finds most of her material on Stinson Beach, north of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. She layers and pastes thousands of pieces of plastic marine debris—everything from parts of cell phones and bottle caps to dental picks and fishing gear—to create mosaic portraits. They are her “playful response to a serious issue.”

Mermaid, by Tess Felix.

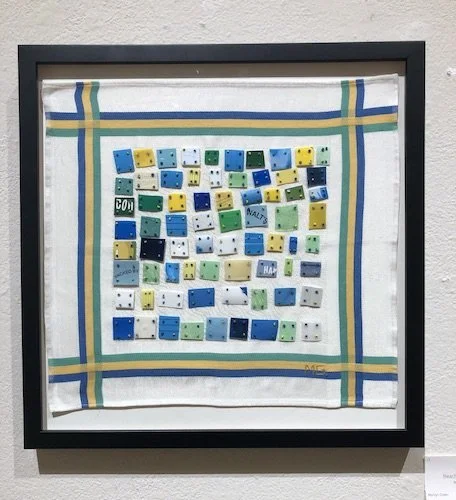

Almost daily, Marilyn Green can be seen peering down at the sand on Pebble Beach at The Sea Ranch, looking for the tiny pieces of plastic as well as sea urchin spines, bits of mussel shell and abalone, and pebbles that she incorporates into her work. They might wind up as a tiny quilt (see image below) or as small scenes that would charm any child.

Beach Plastic Quilt, by Marilyn Green.

Perry Hoffman, a photographer, mosaic maker, tile maker and creator of the Tile House in the Mojave Desert, is another coast artist who has the ability to bring together the most disparate objects and create a composition with them. All Washed Up from Humanity is a perfect example and includes allusions, like Beth Hartmann’s work, to the dirty footprints we leave behind.

All Washed Up from Humanity, by Perry Hoffman.

Paula J. Haymond is a mixed media sculptor accustomed to working with wood, metal, resin, and stones. As is the case with many other artists, plastic is not her medium of choice but she, too, rose to the occasion. While learning how to add one more skill—weaving—to her repertoire, she decided to weave the plastic tape of old mini-cassettes, reminiscent of how they used to get filled up with messages, and to include porcupine quills.

The Mailbox You Have Reached Is Full, by Paula J. Haymond.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

After proposing the plastics exhibit to Gualala Arts, more than a year ago, I couldn’t help but notice and be appalled by how so much of my healthy, even organic, food was packaged in plastic. That struck me as an oxymoron. As part of the educational aspect of the exhibit, on the entry wall we tacked up the plastic netting that too much of my produce is bagged in. I also set on a shelf the clear plastic jars that my probiotic food comes in and filled them with multi-colored caps from bottles of supplements, juice, and so on. The sizes and colors reminded me of candy in jars from my childhood, but clearly This Is Not Candy. I labeled each jar differently: Not Jelly Beans, Not Jujubes, Not Butterscotch, etc. To the left, I posted THE BAD NEWS about plastic as well as THE GOOD NEWS, so that visitors to the gallery would not be completely overwhelmed by devastating statistics. Promisingly, there is research going on to transform plastic into liquid fuel. There is a plastic-eating enzyme and a plastic-eating fungus. There are roads and paths made with recycled plastic. One company is converting seaweed into bioplastic for consumer packaging and another is using beechwood trees to make biodegradable cellulose net bags to hold produce. And Rwanda is the world’s first plastic-free nation. While this is not enough, it’s certainly a start.

My small encaustic hanging in the exhibit, with just a touch of plastic, is a call to all of us to simply Stop Trashing.

Stop Trashing, by Mirka Knaster.

Questions & Comments:

How do you feel about creating artwork with plastic components? Do you use them in your own work?

What artists do you recognize as championing environmental clean-up through their art?